The links between digestion, or disrupted digestion, and mental disease were considered extremely strong by asylum practitioners of the nineteenth-century. A researcher working with asylum records will inevitably be faced by extensive dietary tables, long discussions of force-feeding, and detailed accounts of patient bowel movements. As such, the asylum kitchen was one of the most important parts of the institution. Staff, and often female patients, worked to provide the patients and attendants with food largely sourced from within the asylum grounds itself as institutions because increasingly self-sufficient. Patients’ work was positioned as beneficial for their convalescence, but also played a significant role in reducing the running costs of institutions.

Patient diet was seen as an important part of care, and it was recognised by doctors that malnutrition and poverty played a significant role in diminishing mental health. D. C. Campbell, Superintendent at the Essex Asylum, even encouraged the formation of funds for discharged patients of County Asylums, in order to support healthier living and better opportunity on their release from the asylum; ‘scanty diet’ being one of the challenges in maintaining recovery.1

“A large proportion of the recent cases arrived in a state of ill health, or so much exhausted and reduced in condition that any mode of treatment directed specially to their mental improvement would have been nugatory, until the strength was recruited by a generous diet, and health re-established by remedial or hygienic measures.”

Food was, then, an essential element of treatment. Thomas Clouston became well known for his ‘Gospel of Fatness’, an extraordinary-sounding food-based approach to treatment which saw patients fed enormous quantities of food in order to increase their weight. Allan Beveridge has revealed how this approach was even the focus of some patients’ letters, complaining of being unable to keep up with the eating required of them.2 Rich diets were also used at later so-called imbecile asylums, such as at Caterham - Stef Estoe notes the feeding of custard to patients in the late nineteenth century.3

Nineteenth-century discussions of diet, and its ethics, were linked to religion, philanthropy, and arguments about health and social reform - of which asylums, and moral treatment, were a result. It’s therefore interesting that in the asylum, a place so concerned with moral and physical health, wider debates about consumption and morality seem to have had little impact on medical directive. Meat-eating was facing newly organised criticism in Britain in the nineteenth century. A growing faction of vegans and vegetarians linked the consumption of meat to the consumption of alcohol in what Gregory James has called ‘ultra-temperance.’4 Eating animal products was a gateway to poor moral health, and thus eventually poor physical health.

‘Grand Show of Prize Vegetarians’, John Leech, Punch, 1852 (via the John Leech Archive)

As today, nineteenth-century vegans and vegetarians met with harsh criticism. Some was relatively mild, such as a piece by Punch cartoonist John Leech, who satirised the vegetarian movement in 1852. Others, however, drew on degenerationist concerns that a change in the Victorian diet might disadvantage the ‘race’ as a whole. The Illustrated London News declared that to “preserve the integrity and enterprise of the Anglo-Saxon race, the first medical authorities declare that a full meat diet must be used.” 5

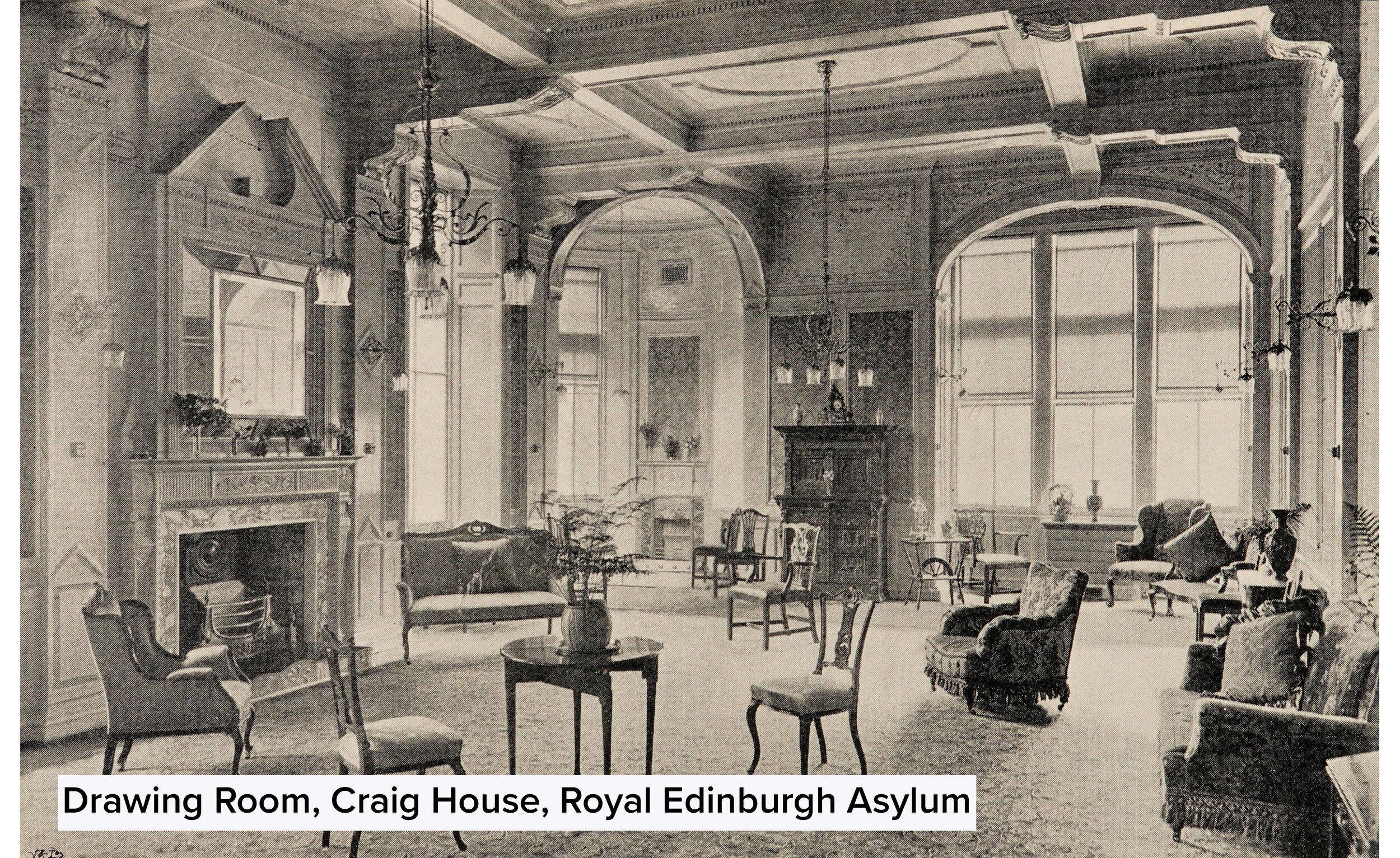

However, the press also allowed proponents of the movement to spread their message: for example, The Vegetarian Messenger was produced by the Vegetarian Society from 1849. Others publications also promoted abstinence from meat and animal products. Martha Brotherton’s Vegetable Cookery was the first vegetarian cookbook, produced in 1812. 6 Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was famously vegetarian, writing in defence of his ‘natural diet’ in 1813 . 7 Vegetarian writing especially proliferated in the late nineteenth-century, with further cookbooks, tracts and books endorsing the practice. And it seems that some vegetarian publications even found their way into the asylums: the Royal Edinburgh Asylum’s library contained John Smith’s Fruits and Farinacea: The Proper Food of Man, published in 1845. This text was an influential one in the world of vegetarianism. It isn’t clear exactly how this book ended up on the shelves of the library, but given that so many texts were received as gifts it seems possible it may have come from a donor. Perhaps the donor, as a supporter of the ‘humane’ treatment of the mentally ill, also considered animals worthy of kinder treatment? Or perhaps they thought that asylum patients – with lunacy so often linked to intemperance – could benefit from encouragement to live according to principles of ‘ultra-temperance’?

An illustration (possibly by R. T. Trall), from the 1854 New York edition of Fruits and Farinacea published by Fowler and Wells (held by Cornell University, digitised by HathiTrust).

Whatever their reasons for donating the book, Fruits and Farinacea made little impact on the Royal Edinburgh’s dietary. Whilst the temperance movement might have had an influence, vegetarianism never seems to have been considered as a path to convalescence. According to the dietary tables and reports by the Commissioners, patients did get their fair share of vegetables, often grown within the asylum grounds. But animal products were common fare - meat and its quality was a regular topic of discussion by both patients and staff. The Committee of the Isle of Ely and Borough of Cambridge Asylum investigated patient diets across several asylums in 1862; one of the results being a comparison of the amount of meat provided. At the Essex asylum, male patients received 42 ounces of uncooked meat per week; Wiltshire gave around half that, at 19.5 ounces; Nottingham provided their patients three vegetarian dinners per week. George W. Lawrence attributes the Cambridge Asylum’s high percentage of recoveries “chiefly to diet,” and goes to far as to include a table comparing ten asylums’ recovery rates with their spending on provisions.8

Other animal products, such as milk and eggs, were also important. Clouston’s ‘Gospel of Fatness’ would have been impossible to implement without them. The pauper diet in Inverness was a cause for concern for staff at the asylum, who worried about the low nutritive value of food due to over-reliance on potato, and fretted about the milk supply. “Nothing is more necessary for the proper treatment of the inmates of this asylum than a full supply of milk,” wrote Scottish Lunacy Commissioner John Sibbald. “It is not going too far to say that a deficient supply will, in many cases, prevent the recovery of the patients […]”9

Digestive system: twelve figures, including teeth, intestines and colon. Line engraving by Kirkwood & Son, 1813. (Wellcome Collection)

In the medical sphere, texts like Smith’s Fruits and Farinacea had received a largely negative response – few were convinced by Smith’s claims that meat was "prejudicial to man’s health and well-being.”10 Whilst the book was commented on by medical journals such as The Medico-Chirurgical Review, it seems to have made little impact on the world of the asylum doctor. In the asylum, the patient diet should be nourishing, wholesome, and sufficient to maintain weight and challenge the impact of malnutrition. Little explanation is made as to why meat or fish are chosen; the question of why John Sibbald was quite so enamoured with milk, is not clearly answered in any of his reports. It may have been the fact that vegetable matter, harder to digest, was seen by some as requiring “greater power of the gastric organs,” which those suffering from lunacy were often deemed not to have.11

“It is undoubtedly true that food prepared in the form of Soup or Stew is not generally relished by the labouring classes in this country. [The Stew] contains an abundance of meat, yet [the Commissioners] correctly remarked that some patients refused it wholly or in part. Probably this may be dependent to some extent on an idea that refused articles of food are again employed in the preparation of Soup.”

On the whole, discussions of patient nutrition focused how much patients should be given, rather than what exactly they should eat; and Commissioners’ complaints about asylum dietaries revolved around whether patients liked the food enough to eat it. Ultimately, much of the patients’ experience with food was decided by practicality rather than morality: what could be produced in-house, what would be cheap, and what wouldn’t be wasted.

Sources:

(1) D. C. Campbell, Report of the Medical Superintendent, Annual Report of the Essex Asylum for the year 1856, p. 15.

(2) Allan Beveridge, ‘Life in the Asylum: patients’ letters from Morningside, 1873-1908’, History of Psychiatry, ix (1998), p. 440.

(3) Stef Estoe, Idiocy, Imbecility and Insanity in Victorian Society: Caterham Asylum, 1867-1911 (Palgrave, 2020), p. 81.

(4) James Gregory, Of Victorians and Vegetarians: The Vegetarian Movement in Nineteenth-century Britain (Tauris Academic Studies, 2008), p. 5.

(5) llustrated London News, 15 June 1851, p. 560.

(6) Martha Brotherton, Vegetable Cookery (E Wilson, 1833), first published in periodical form in 1812.

(7) Percy Bysshe Shelley, A Vindication of the Natural Diet (1813)

(8) George W. Lawrence, Report of the Committee, Annual Report of the Cambridge & Ely Asylum, 1862, p. 9.

(9) Thomas Aitken, Report of the Medical Superintendent, pp. 14-15; John Sibbald, Report of the Commissioners, p. 4; Annual Report of the Inverness District Asylum for the year 1889.

(10) John Smith, Fruits and Farinacea: The Proper Food of Man (Fowler & Wells, 1854), p. vii.

(11) Jonathan Pereira, A Treatise on Food (Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1843), p. 525.

Other useful material:

Onno Oerlemans, ‘Shelley's Ideal Body: Vegetarianism and Nature,’ Studies in Romanticism 34.4 (1995) 531-52.

Madeline Bourque Kearin, ‘Dirty Bread, Forced Feeding, and Tea Parties: the Uses and Abuses of Food in Nineteenth-Century Insane Asylums’, Journal of Medical Humanities (2020) (open access)

Sarah Chaney, “Fat and Well”: Force-Feeding and Emotion in the Nineteenth-Century Asylum, The History of Emotions Blog, 2012

Glenside Museum, ‘Good roast beef with potatoes, cabbage and gravy’: Asylum food 1861-1900