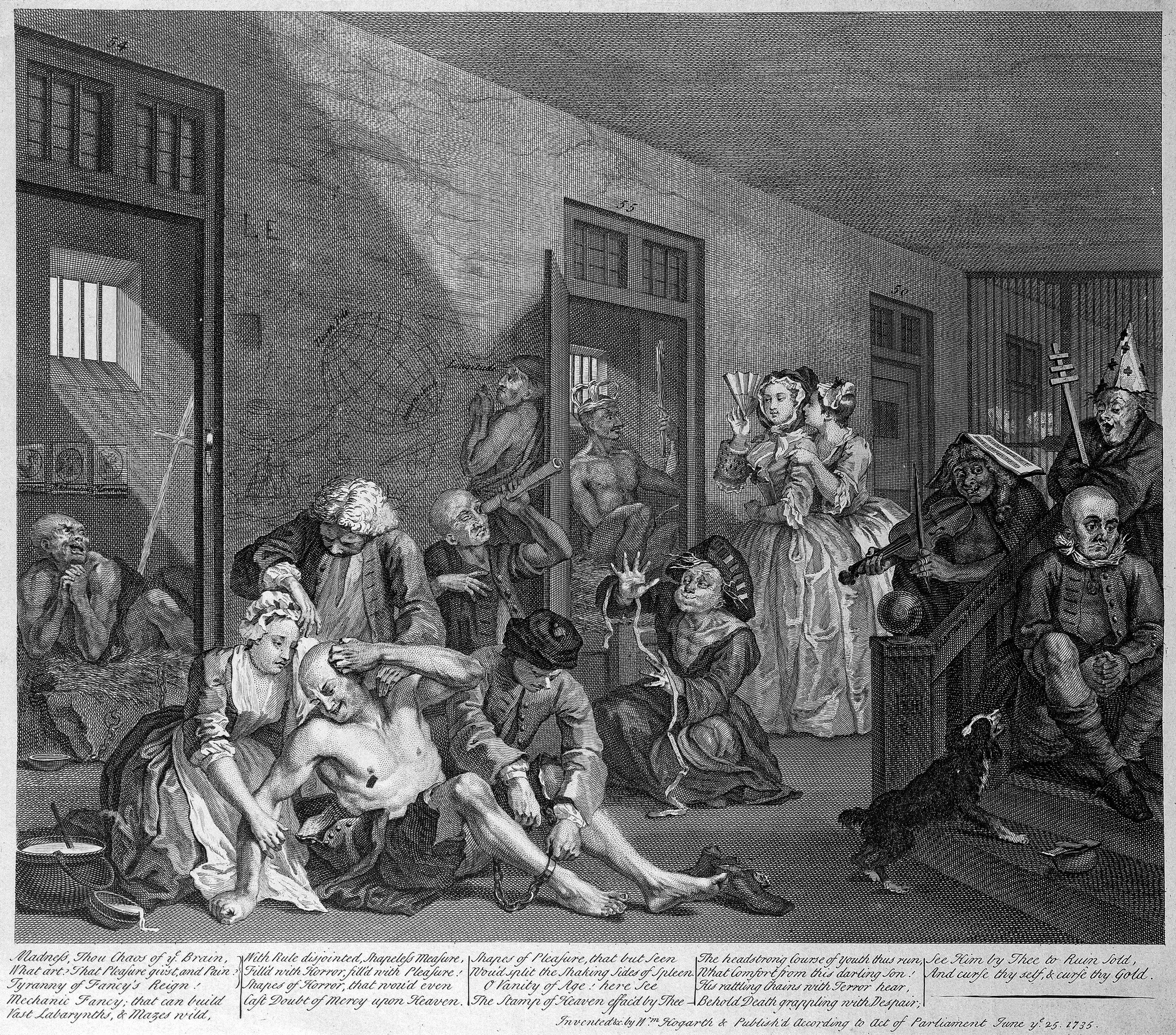

'Hogarth's The Rake's Progress; scene at Bedlam.' by T. Cook. (Wellcome Collection, CC BY)

Our cultural conception of the asylum paints it - often fairly - as a place of unjust confinement and institutional abuse. When we talk about something being in a state of chaos or irrationality, we might describe it as ‘Bedlam’ - a word derived directly from the name of London’s Bethlem Royal Hospital.1 Long before the advent of ‘moral treatment’ in the late eighteenth century, and its widespread use in the nineteenth century, the asylum had already gained a reputation as either somewhere to be feared, or for the more fortunate, somewhere to visit on a day trip to gawp at ‘lunatics’.

Samuel Bruckshaw, One More Proof, written in 1774 following what he considered to be an unjust confinement in a private madhouse in Lancashire. (Stanford University Library, digitised by Google)

Historically, those deemed to have mental illnesses and intellectual disabilities might have been looked after in their communities, by family or charity - or, as the case was for many poorer people, not looked after at all, ending up on the street, in prison, or the workhouse. As the ‘trade in lunacy’ developed considerably through the eighteenth century, private madhouses began taking over responsibility for those deemed mentally ill.2 These for-profit institutions tended to operate under policies of discretion, allowing families who could afford it to limit their caring responsibilities and avoid the stigma associated with having a relative with mental illness. However, the secrecy surrounding private madhouses could enable abuse, with patients treated inhumanely and kept in dire conditions.3 Wrongful confinement was at the forefront of public imagination and remained so throughout the nineteenth century, exemplified by public interest in cases such as Rosina Bulwer Lytton’s and captured in literature like Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White.4 Public institutions, growing in number throughout the century, also provided the public with plenty of anxiety; many faced criticism and public exposés of their treatment of patients and use of mechanical restraint.

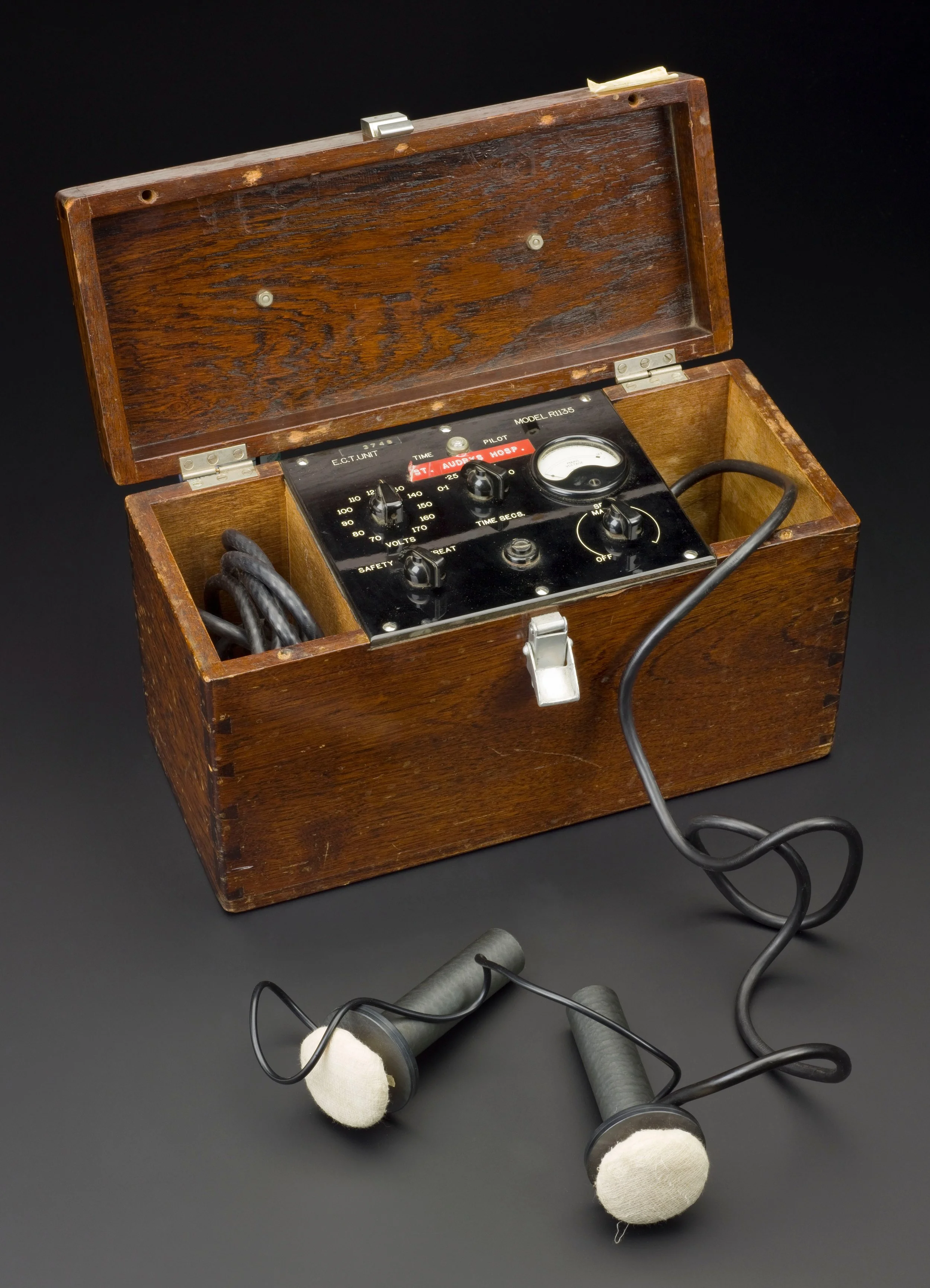

Electroconvulsive Therapy Machine, (Science Museum, London. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.) Source: Wellcome Collection.

Twentieth century asylum-based treatments moved increasingly towards medicinal and surgical intervention. Physical treatments were used in asylums prior to this point, but methods became even more experimental as asylums became training centres for students and doctors aimed to provide cutting edge treatments.5 Techniques such as electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), insulin shock therapy, and the now infamous prefrontal lobotomy gained traction. However, many of these procedures are now widely recognised to be both inhumane and largely ineffectual in most cases. Over the course of the century, deinstitutionalisation grew in popularity as part of an antipsychiatry and disability rights movement, and asylums began to close. In the UK, this process began wholesale in the 1980s with Thatcher’s ‘Care in the Community’ - though whether this change has been successful in improving conditions for mentally ill people in Britain is contested.6

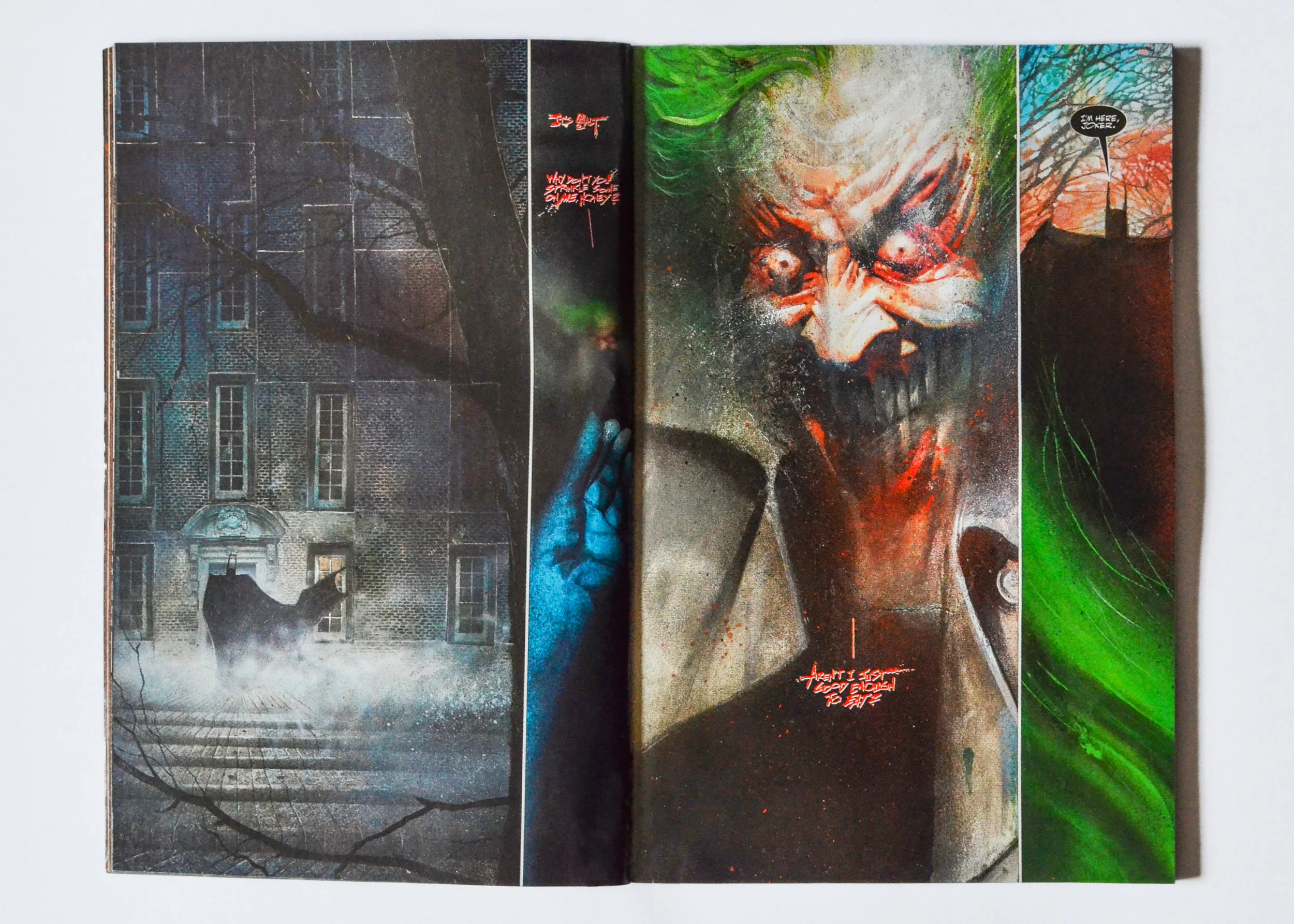

In the twenty-first century, with the asylum system largely long gone, the ghost of the institution retains its strong influence on culture - and the abuses of previous eras are certainly not forgotten. Mention the word ‘asylum’ and most people’s minds will jump to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, or possibly DC’s Arkham Asylum. Wrongful confinement remains a common trope for the thriller and horror genres, such the committal of lesbian journalist Lana Winters to the terrifying Briarcliff Manor of American Horror Story. With many asylum buildings in Britain and Europe now simply abandoned, they have also become an object of fascination for ‘urban exploration’ photographers documenting the remnants of our institutional history, and paranormal enthusiasts convinced they’ll find apparitions of patients past. Most media now relies on three stereotypes of the asylum: the ‘olden days’ of Bedlam-like institutions and shackled patients; the drastic medical interventions of early twentieth-century; and the abandoned ruin, relic of a time gone by. But is this terrifying picture of the asylum a complete one?

Grant Morrison, Arkham Asylum: a serious house on serious earth, illustrated by Dave McKean (DC Comics, 2014)

Sources:

1 Jonathan Andrews, Asa Briggs, Roy Porter, Penny Tucker and Keir Waddington, The History of Bethlem (Hove: Psychology Press, 1997).

2 William Parry-Jones, The Trade in Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (London: Routledge, 1972).

3 Roy Porter, Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A History of Madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency (Penguin Books, 1990).

4 Rosina Bulwer Lytton, A Blighted Life (The London Publishing Office, 1880), full text available online at Wikisource.

5 The Mental Health History Timeline, developed by Andrew Roberts at Middlesex University, provides a very thorough outline of the history of mental health treatment from pre-history to the present day.

6 Robin Means, Sally Richards and Randall Smith, Community Care: Policy and Practice, 4th edition (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Other interesting reading:

Birkbeck’s excellent teaching resource, ‘Deviance, Disorder & the Self’, in particular the ‘Wrongful Confinement’ section

Jade Shepherd’s blog, ‘Voices from Broadmoor’, including these posts focusing on wrongful confinement at the institution

This post by Jennifer Crane for Warwick University’s Centre for the History of Medicine, on patients’ perceptions of their confinements